5 Speeling and Grammer Mistake’s That Can Justify Murder

If the title to this blog post didn’t make you want to punch something or, at the very least, cringe slightly, you have a stronger constitution then me … and if you noticed the mistake in the previous clause, you’ll probably appreciate this post. But, before I get onto the listing bit, which we on the internet so love, I want to say write type a few things to let you see where I’m coming from.

Language fascinates me. The way languages evolve is something which I’m particularly interested in. Unfortunately, this creates a problem for me; you see, language evolution happens in a similar way to biological evolution: through mistakes. Just as errors in the process of copying DNA can turn a dinosaur into a chicken, so too, errors in language acquisition can turn Latin into French.

Of course, it’s more complicated than that, but the cumulative effects of generations upon generations of mistakes is one of the main reasons that we can’t makes heads or tails of something like Beowulf.

So why is that a problem? Well, mistakes – particularly in language – can be very annoying. My theory is that it’s related to the uncanny valley effect: a minor difference in something as familiar as your native tongue gets your brain all riled up.

No-one gets annoyed that the French say souder instead of solder – who ever really expects to understand the French? – but when another English speaker drops¹ the l, it’ll at least make you sit up and think, “hang on…” if not actually annoy you.

Your brain’s happily following along, everything’s obeying the rules you know and love, nice and predictable as the brain likes it, then you hit a linguistic speed bump and your brain resets to its default mode: KILL. CRUSH. DESTROY.

Note: I don’t have a problem with linguistic innovation which enriches the language and makes communication easier and/or more fun. What I dislike is errors which confuse meanings and generally make communication harder. So, without further ado², let the list begin.

¹ If your accent does drop the l, read that as “pronounces the l” instead. Also, stop dropping the l. They put it in there for a reason. What are you, French? Jeez.

² Apart from that note above this one. And this note.

5. Saying could care less instead of couldn’t care less

Why it’s annoying:

You’re saying the opposite of what you mean.

I know, I’m not the first to complain about this and I’m sure I won’t be the last, but please, just stop doing it.

Why it’s OK:

If you say this wrong, it’s probably because you grew up with it. Just as in phrases like “at sixes and sevens” or “beat you to the punch”, you likely just internalised it as an idiomatic expression with a set meaning, never looking at what the literal meaning of the phrase was.

Why it’s really not OK:

The moment someone explains to you that “could care less” means that you do care, not that you don’t care, which is what you meant to say, you should instantly stop saying it.

If everyone just stops making the mistake, it will go away. If you keep on saying it wrong, you’ll teach it to your kids wrong and they’ll teach it to their kids wrong and before we know it the whole world will have gone to hell in a hand basket. And the logistics of finding a hand basket big enough to fit the entire world within are bad enough without even getting into the non-existence of hell.

4. Thinking then and than are the same word

Why it’s annoying:

Then and than are not the same word.

Do I really need to explain this? Saying “I’d prefer to have my legs cut off than my head,” is perfectly reasonable. Given the choice between either losing my legs or losing my head, I would rather the one which doesn’t kill me. If I said that “I’d prefer to have my legs cut off then my head,” on the other hand, the best interpretation would be that I want my legs cut off first, then I want my head to be cut off after.

Than is used in comparisons. Then is used when you’re talking about when or in what order something happens.

God. Damn. It.

Why it’s OK:

Firstly, it’s an understandable mistake. It’s a lot like the common mix-up with effect and affect. In speech, both words tend to be unstressed and reduced to /ðən/, making them homophones.

Not only that, but Shakespeare did it. In fact, then and than once were both the same word. They both evolved from Old English þanne, meaning “then”, “when” or “because”. The comparative meaning probably evolved from something along the lines of “A is bigger, then B”, as in A comes first in bigness, then B follows it.

Why it’s really not OK:

You know what? Just because Shakespeare did something, doesn’t make it alright for you to do it. Shakespeare lived in the sixteenth century; he probably shat in a bucket then tipped it out his window. Now, I don’t know where you live, but it’s almost certainly not alright for you to do that.

Secondly, if you’re going to use their having once been the same word as an excuse for being wrong now, I’ll ask that you use the same logic throughout the language and stop distinguishing between can and know, which both come from the same Proto-Indo-European root: *ǵneh₃-.

3. Using lay when you mean lie

Why it’s annoying:

OK, I understand this; it’s an easy enough mistake to make and we’ve all probably done it before. But if you’re writing a book, an article, a song or anything like that, do a little proof reading first. Please.

I’m looking at you, Bruno Mars.

You don’t “just wanna lay in your bed.” Assuming you’re not a god-damn hen, you wanna lie in your bed, you…stupid…fuck. I actually kinda like that song too, but every time it gets to that line, I want to find you and shoot you in your stupid can’t-speak-proper-English face.

OK, fine. Maybe that’s an overreaction. Pop-stars aren’t supposed to be the smartest people around, I know, but it would be nice if they could put a little effort into speaking the language. I mean, come on. Think of all the kids listening to this song on the radio and getting it into their heads that lie and lay are interchangeable. They are not.

Why it’s OK:

If someone’s just speaking casually, this is the kind of error that can be easily overlooked. It’s a funny quirk of the language that lay happens to be both the past tense of lie and a verb all on its own and it’s easy to see how you can mix them up every now and then in the heat of a conversation.

Why it’s really not OK:

It kind of is OK, but only – and I cannot stress this enough – only in casual conversation. It is not OK in any medium where you have a chance to go back and correct your glaring errors, like in a song, where it’s NOT FUCKING OK, BRUNO MARS, YOU DICK.

And speaking of annoying mistakes that pop artists make…

2. Using gotta when you mean got a

Why it’s annoying:

Gotta is a fine word. When you’ve gotta contract got to, it’s the go to; nothing beats it. But that is what it’s for: contracting got to. It’s not a substitute for got a. That’s not even a contraction. It’s exactly the same if you say it and the only thing you’re doing typing it is swapping the space with a t.

There is nothing more convenient about using gotta instead of got a and it’s just plain wrong. Sorry; this post wasn’t meant to be about insulting pop artists, but Black Eyed Peas (I don’t know your individual names and don’t care to find out), all of you deserve to die for that song.

Why it’s OK:

It’s not OK. It’s not ever OK.

Why it’s really not OK:

Will.i.am. I lied. I know his name. What an arsehole. What a stupid, fucking, fail-at-English, piece of shit. Fuck you, will.i.am. (I don’t even know if he’s the one who wrote it, but he almost certainly had a say and he just strikes me as an arsehole. What kind of person sues someone over the phrase “I am”? An arsehole. Also that iPhone camera thing… what? You have no association with photography or cameras, will.i.am; you’re lucky anyone even calls you a musician. Oh, and do I even have to mention the name? And really, who actually likes the Black Eyed Peas? Like, what kind of person would call themselves a Black Eyed Peas fan? They’re not terrible or anything, but they haven’t released a single song I would choose to listen to since “Where is the Love?”. I know, 12 year olds will buy whatever they hear on the radio, but who decided to play that shit on the radio to begin with? Why are you even still reading this? I’ve gone so far off topic, I don’t even know what I’m writing about any more.)

1. Writing of when you mean have

Why it’s annoying:

AAAAAAAAAHHHHHHHHHHH!!!!!!!

Why it’s OK:

IT’S NOT OK!!!!!!!!

Why it’s really not OK:

Why the Nexus 7 isn’t worth your time and money… yet.

The Selling Point

On paper, the Asus made Google Nexus 7 is a lovely piece of hardware. 2GB of RAM, a 1920×1200 pixel display with a stunning 323 pixels per inch, and of course a 1.5 GHz quad-core Snapdragon S4 Pro processor. All this for $339 (AUD) really does pack a punch.

So where could this deal go wrong?

User reports of erratic touchscreen issues are widespread and it is clear that it is not something that effects just a few devices. Google stated it released a fix for the issues in a JSS15Q update. This “fix” certainly didn’t fix my Nexus 7. In fact, some people from the lengthy Google thread stated that the JSS15Q/J triggered the bug for them.

When users are not holding the device, the touch screen registers two touches as three, four or five; or worse, registers one as two! There have also been reports of phantom touches, swipes and freezes.

Furthermore reports over Whirlpool and XDA forums are suggesting that there could be quality control issues given the large amount of devices with dead pixels, dust under their screens and GPS issues.

The Nexus 7 2013 was by far the best tablet I have ever used. I want to make that clear. However, if Google wants to retain its customer base to remain loyal and ensure sales keep on a good trajectory – they need to make sure issues like this aren’t happening.

I returned my Nexus 7 for a Note 8 and have not looked back since. Sure, I need to get used too TouchWiz, but at least it is working. My verdict? If you want one of these bad boys, wait it out. Don’t fork out your hard earned bucks just yet.

Status Update: Lateness, New Series and New Podcast

Just a quick message from me, Michael, explaining why we are running a bit late and plans for a new season. Have a listen if you care to know what is going on in the world of Brain Exchange. Link to MP3 here

Brain Exchange S02E06

Let’s Conlang – Part III “Solemn Vowels”

Welcome back to Let’s Conlang! Last post, we worked hard on giving our conlang some totally radical consonants, but our language doesn’t have any vowels yet and without vowels a language is just lngg …. so, uhh… yeah. Vowels. Let’s get some of those.

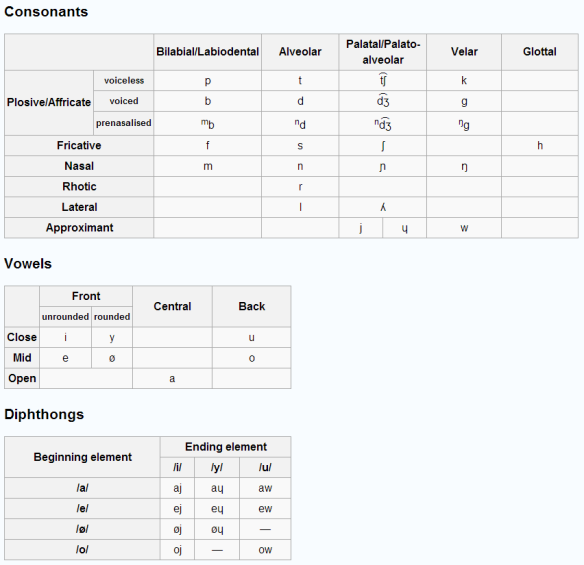

Vowels

Before we start talking about vowels, I want you to forget everything you know about vowels in English, because English vowels are an absolute mess and generally spelt in the most unintuitive way possible¹. Second, go listen to these vowel samples. It’s not really that important for this post, but it is pretty fun trying to make them sing hot cross buns or something.

Now, in natural languages, vowel systems can range from the very simple (e.g. Arrente, an Australian Aboriginal language with only two vowels) to the very complex (e.g. Danish, which has infinity-million). For our conlang, I think it would be nice to do a goldilocks and go for something in the middle, so let’s get started.

If you went to that link I linked or spent some time looking at the vowel section of your IPA chart, you might have noticed the words close, mid and open along one axis and front, central and back along the other. These are basically describing the position of your tongue when you articulate² the sound.

The first set says how high your tongue goes while you articulate the vowel. For example, /i/ and /u/ are close (or high³) vowels because the tongue is held high or close to the roof of the mouth (depending on which terminology you prefer) when you say them. Similarly, /a/ and /ɑ/ are open (or low³) because the tongue is held low or such that the mouth is more open (hence doctors telling you to “say ah”). And, between the two extremes, we get our mid vowels like /e/ and /o/.

The other axis which decides what a vowel sounds like is that of front-/backness. On this axis, /i/ is front because it’s pronounced with the tongue pushed forward and /u/ is back because it’s pronounced with the tongue pulled back. In English the central vowels are reduced vowels like /ə/ (the unstressed e in cromulent⁴).

As with most matters of phonetics, the best way to quickly understand what’s going on is to try it out. Try saying beat and compare the vowel to that in bet and that in bat. You should notice that your tongue gets progressively lower for each. Now compare beat and boot and you should feel your tongue moving back in your mouth.

OK, enough tonguing; it’s time to give the lips some attention. The third way that vowels can be differentiated is by their rounding. When articulating a rounded vowel, like /u/, the lips are – you guessed it – rounded. And when articulating an unrounded vowel, like /i/, they’re not.

In English, back vowels are rounded and front vowels are unrounded, so we don’t really have to worry about distinguishing vowels only by their rounding, but a lot of languages do make the distinction and, fortunately, it’s one that is quite easy to pick up, even for English speakers.

Short Vowels

Right, so that’s enough introduction. Let’s get to picking our vowels. Let’s start with the most common vowel around: /a/⁵. Now, not all varieties of English have this vowel, but in Australian English (my dialect), it’s the vowel in cut. If you’re familiar with Spanish, French, Italian, Japanese, German, Polish, Turkish, or pretty much any other language, it’s the sound of the vowel a.

(Note that the English examples in the next few paragraphs are generally approximations. Refer to the vowel samples linked above if you want a more precise idea of what the vowels sound like.)

As you’ll recall from our work with consonants, phonology is all about which differences are going to be meaningful and the most commonly used distinction in vowels is height, so let’s go with that first. We’ve already got an open vowel (/a/), so let’s grab a mid vowel, /e/ (the e in bed), and a close vowel, /i/ (the i in bid), to go along with it. Sweet.

We could go on to have a distinction between close-mid and open-mid vowels, like a lot of languages do, but in the interests of making this language easier to speak (and write down), we’ll just stick to the three heights.

Now, let’s use our second axis and make some back vowels: a mid one, /o/ (the o in bod), and a close one, /u/ (the oo in boot (not the u in bud)). You’ll probably notice both of these are rounded. That’s because it’s not just English that likes to round its back vowels; it’s a pretty common feature of most languages.

Now, most languages also tend to just leave rounding to the mid-to-high back vowels, like English does, but that’s a bit boring, so let’s also add ourselves some rounded front vowels, namely /y/ (the rounded version of /i/) and /ø/ (the rounded version of /e/)⁶.

But how the hell do you say those? It’s not as bad as you might think. Just say /i/ and /e/ but with your lips rounded at the same time. If it helps, /y/ is the u in French zut and /ø/ is the eu of sacrebleu.

Cool. We’ve got seven vowels now, but hang on. A language is a system where the sounds are there for a reason, not just because someone threw them in there⁷. Why would we have these rounded front vowels? My solution: palatalisation.

Without going too far off-track, let’s just say that /y/ and /ø/ evolved from historical /u/ and /o/ preceded by a palatal consonant. Don’t worry if that doesn’t make sense to you now; we’ll probably get into it in more detail next post.

Long Vowels

Next up are long vowels. If you didn’t remember to forget everything you know about English vowels, you might be thinking a long vowel is like the i in bite. That’s not a long vowel; it’s a diphthong. (Be patient. Diphthongs are coming up soon.) You might also think that a long vowel is like the ee in feet. That one is a long vowel, but it’s not a long e, it’s a long i.

All the confusion with English spelling might make long vowels seem complicated, but they’re not really. A long vowel is exactly the same as the short version of that vowel, but you keep saying it for longer. For example, English bit has a short /i/ and English beat has a long /iː/. (Once again, English let’s us down, because the i in bit is actually slightly centralised and lowered to /ɪ/, but let’s ignore that.) The “ː” bit here is what tells you the vowel is long. If you look closely, you’ll see it’s not quite a colon⁸, but if you use a colon instead, everyone will know what you meant.

In our conlang, we could just let every vowel be either short or long, as is the case in Latin, but let’s instead tie vowel length in with stress. We’ll get into stress when we start working on the prosodic features of our language, but for now we’ll just leave it as a vowel is long if it’s in a stressed open syllable and short otherwise.

With both short and long vowels handled, you might think we’re almost ready for diphthongs, but before we get into them, I’m going to jump back a bit to our consonants. Specifically, the approximant consonants which we looked at last post, but couldn’t finish until we’d got our vowels sorted.

Semivowels

Semivowels are basically the consonants that you can make by putting your tongue in the same place that you would for their corresponding vowel. English has two semivowels: /w/ (the w in water, corresponding to /u/) and /j/ (the y in you, corresponding to /i/). These are the two most common semivowels and, since our conlang has both /i/ and /u/, it makes sense that we’ll have /j/ and /w/ too.

You may have noticed that these semivowels correspond to our close vowels and our conlang has another close vowel: /y/. You will be pleased to find out that, indeed, there is a semivocalic version of /y/ and it’s represented in the IPA by /ɥ/ (an upside-down h). To figure out how to say that, just say /j/ but with your lips rounded.

Now, what about the other vowels? Are there semivocalic counterparts to /e/, /ø/, /o/ and /a/? Well…. yes, there are, but most of them don’t occur in many (if any) natural languages. Semivocalic /e̯/ and /o̯/ do occur in Romanian, but being so similar to /j/ and /w/, they are very rare cross-linguistically. It’s a similar story for /ø̯/, which is too similar to /ɥ/. As for /a/, it’s hard to say. It’s possible to have a semivocalic /a̯/, but I’ve not come across any evidence of a natural language using it.

Diphthongs

And finally, we reach diphthongs. I love diphthongs, mostly because they give me an excuse to use my favourite ever sequence of sounds: /fθ/⁹. You can also pronounce it “dipthongs”, but what kind of horrible monster would even contemplate such a heinous act?

Diphthongs, from Ancient Greek di- “two” + phthongos “sound”, are literally that: two vowel sounds put together into one super-powered-mutant-vowel-thing! Examples in English are /ai̯/ (the igh in sigh), /au̯/ (the ou in sound) and /ei̯/ (the ey in grey). These are “falling” diphthongs, so called because their second element is less prominent. “Rising” diphthongs such as /i̯a/ also exist, but since we won’t be having any in our conlang, I won’t go into them here.

The above English examples are all also closing diphthongs, so called because they end in a closer vowel than they started with. In addition to these, non-rhotic dialects of English (such as Received Pronunciation or Australian English) have centring diphthongs like /iə̯/ (as in fear) and /uə̯/ (as in pure). Once again, we won’t be having these in our conlang, so I won’t go any further into it.

(Note that the little bump¹⁰ below the vowel indicates that it’s the less prominent element of the diphthong. Another way to show this is by using the symbol for the semivowel for the less prominent element; that’s what I’ll be doing from here on.)

What we will have in our conlang are diphthongs which are both falling and closing; that is, they’ll all end with one of our close vowels. The first three will be the ones starting with /a/: /aj/, /aɥ/ and /aw/. Now, moving up to start on the mid vowels, we’re going to avoid mixing /y/ and /ø/ with the back vowels (because it wouldn’t make sense from the sounds’ histories), so we get: /ew/, /ow/, /ej/, /øj/, /oj/, /eɥ/ and /øɥ/.

So there we go: seven monophthongs (our short vowels) and ten diphthongs. That’s our vowels done and the last of our consonants done too.

And, with that, we can make some nice pretty tables illustrating all of our phonemes:

Next post, we’ll come up with an orthography and start setting out the rules for how these phonemes can be put together to make our language’s words. Stay tuned!

– Ben xoxo

Notes

¹ Yes, I’m aware that I’m being somewhat hyperbolic here, but English is certainly one of the least sensibly spelt languages in the world (slightly behind Icelandic). In case you’re interested, the main reason our spelling makes so little sense is that most things are spelt as they were said in the late fifteenth century, so, on the bright side, at least it’s easier to figure out how people spoke during the Wars of the Roses…. I guess.

² Or “say”, if you insist on using confusing technical terminology.

³ A lot of linguists like to avoid using the terms high and low to describe tongue position because they think it will make the low vowels feel bad. Also, it can get confusing when you’ve also got high and low tone going on.

⁴ Note that cromulent can also be pronounced with a syllabic n, instead of the sequence /ən/ and, most of the time, is. But it’s a good word, so whatever. Sue me. (But don’t, ‘cos I have no money.)

⁵ The IPA symbol a can stand for any vowel between front /a/ and central /ä/. The difference isn’t that big and for our conlang, we don’t really care which it is.

⁶ The kind of rounding we’d find on these front rounded vowels would probably be with the lips compressed, rather than the protruded rounding of back vowels, but that’s a minor detail which we needn’t really worry about.

⁷ Which is, technically, a reason, but not a very good one if we’re trying to imitate natural language. Work with me here.

⁸ Although Unicode calls it “modifier letter triangular colon”, it’s clearly actually “two tiny triangles pointing at each other”. There’s also a half-long symbol which looks like this: ˑ. Just one tiny triangle on that one. Yep.

⁹ Another good word for the /fθ/ combination is phenolphthalein, which is even better because it has both in the onset of the same syllable. Just say it with me; phenolphthalein. Beautiful, isn’t it?

¹⁰ Unicode calls it a “combining inverted breve bellow”, but what would Unicode know? It thinks the length sign is a colon. Silly Unicode. (Sorry, Unicode, I still love you, baby.)

Brain Exchange S02E05

Brain Exchange – S02E05 (Perma Download Link)

Articles and websites discussed in this episode come from the following:

Let’s Conlang – Part II “Let’s Get Phonetical”

In the last instalment of Let’s Conlang, I went through the basics of what conlanging actually is, then gave you a very basic primer on phonology, phonetics and all that good stuff. You might want to open that in another tab now just to have the IPA chart on hand, but just because I’m an awesome guy, I’ll also link you to the Wikipedia article on each group of sounds we use as we start the epic* process of…

Building a Phonology

The first step in building a phonology is to decide which distinctions are going to be meaningful. Will, say, the difference between [pʰ] and [p] be enough to create a minimal pair¹ (as in Ancient Greek φόνος /pʰónos/ “murder” vs. πόνος /pónos/ “work”) or will it be allophonic² as in English?

There are infinity and one different distinctions you could use building the phonology of your conlang (don’t question it; I’ve counted them all), but a lot of them are unlikely to ever occur in a natural language and a lot of those which do occur in natural languages can be very hard to pronounce.

Sure, there’s nothing stopping us from making a language with two hundred consonants and no vowels or something equally outlandish, but while that could be fun, for our purposes here, I think it would be nice to create a language that we have some chance of being able to pronounce. So let’s begin, starting with…

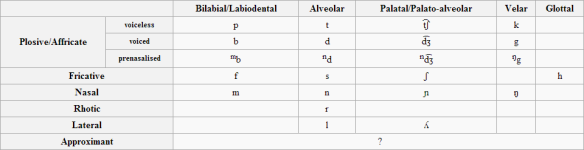

Consonants

1. Plosives

Let’s start with plosives, since pretty much every language has at least one of these. The most common plosives cross-linguistically are /p/, /t/ and /k/³, so let’s start with those. Now a very common distinction for plosives is voicing, so let’s add voiced variants of our plosives: /b/, /d/ and /g/.

Now we’ve got six plosives, but that’s a little boring. We want to imitate natural languages, but we don’t want to be sheep, blindly conforming to the corrupted norms of a soulless society, lead to the slaughter by the consumerist mass media and politicians whose only allegiance is to rapacious corporations, drowning in the fetid taint of world rotten to its core! … or something. So let’s add another distinction: prenasalisation.

A prenasalised plosive is basically exactly what it says on the tin: there’s a nasal sound before the plosive (much like the sequence nd in hand but functioning as a single unit). We could double our plosives here, by having prenasalised voiceless and voiced plosives, but let’s just go for one prenasalised series. Since nasals are naturally voiced sounds⁴, it makes sense to have a series of prenasalised voiced plosives, giving us /mb/, /nd/ and /ŋg/ for a total of nine plosives.

These prenasalised plosives are going to have some interesting implications for the distribution of some sounds in our language, depending on how we decide they could have come about, but we’ll get to that later. For now, we’ve got our plosives sorted, so let’s get onto another method of articulation: fricatives.

2. Fricatives

Less than 10% of languages in the real world lack fricatives (with most of these being native languages of Australia and New Guinea), so it’s probably a safe bet to include some in our conlang. Languages often have fricatives in the same places of articulation as their plosives⁵, so let’s give ourselves some fricatives: /f/, /s/ and /x/ (the ch in loch or Bach), corresponding to /p/, /t/⁶ and /k/ respectively.

But we wouldn’t want to stop there. So let’s add ourselves another. When it comes to fricatives, we’re really spoiled for choice: there’s a whole bunch of them and they’re mostly not too difficult to pronounce. For our purposes, one more fricative should be all we need, so let’s pick something nice and typical: /ʃ/ (the sh in ship).

Now, we have a choice here whether we make voicing a phonemic feature of our fricatives or not. Unlike with our plosives, here I’m going to go with no voicing distinction. As in Old English, the fricatives will be voiced intervocalically and when adjacent to voiced consonants, but the voicing will be entirely allophonic.

That might sound like an odd decision, but there are two good reasons for it: firstly, it’s different to what we’re used to in (modern) English, making it more interesting, and, secondly, the distinction is actually only found in about a third of the world’s languages, so we’ve got fairly good grounds for not making it here.

So, those four fricatives bring our total consonants up to thirteen, which is a lot more than Central Rotokas’ six, but still a far cry from English’s twenty-four⁷. So where to from here? There’s the sonorants, which we’ll get to soon, but there’s one more set of obstruents left to look at first: affricates.

3. Affricates

Affricates are funny little things. With only a cursory glance over an IPA chart, you might even miss them completely; they tend to get tucked away off to one side, or relegated to a footnote, but affricates are pretty common cross-linguistically and they’ll be an important part of our conlang. An affricate is basically just a plosive which is released as a fricative and diachronically they often develop from plosives which have been mutated by various processes⁸. How our affricates developed is not that useful to know right now, but it will come to be important later, so it’s good to keep it in the back of your mind.

A whole range of affricates are possible, but most of them are fairly rare. The most common by far are those with /t/ as their plosive element, so let’s roll with that. I know I said it doesn’t matter where the affricates came from, but it actually kind of does, it’s just not something we’ll be getting into quite yet, so just take my word for it that we’re going to want three affricates: /t͡ʃ/ (the ch in chair), /d͡ʒ/ (the dge in bridge) and /nd͡ʒ/ (similar to the nge in hinge), corresponding to our three types of plosives (voiceless, voiced and prenasalised).

OK, so all the obstruents are finally done. Now it’s time for sonorants.

4. Nasals

Nasal consonants are extremely common; there are virtually no languages without at least one⁹. In fact, /m/ and /n/ are two of the most common phonemes in the world. With that in mind, our language is going to have /m/ and /n/, for sure.

Now which other nasals we’re going to have (if any) is much more interesting. About half of the world’s languages have /ŋ/ (the ng in fornicating) and since we have /g/, and /ŋg/, it makes sense to have it in our language. Another cross-linguistically fairly common nasal is /ɲ/ (the ñ in piñata); we’ll take that too, giving us four nasals: /m/, /n/, /ɲ/ and /ŋ/.

Easy. Next?

5. Laterals

Lateral consonants are basically L-ish consonants¹⁰, so it should come as no surprise that the most common lateral consonant is /l/ (as in the L and possibly the l in Lando Calrissian¹¹). We’ll take one of those and, since we have a palatal nasal, it makes sense for us to get the palatal lateral /ʎ/ (which is not a lambda (λ), but a y turned 180°) as well.

The above two sounds are lateral approximants. There are also lateral fricatives, affricates with lateral releases, lateral flaps and even lateral clicks and ejectives. Most of these are pretty rare (though the fricatives aren’t too so) and, since we’re not going to be having any of them in our conlang, I won’t bother going into them here.

6. Approximants

So we’ve just seen some lateral approximants, now it’s time for the regular kind of Approximants. Approximants are odd; they’re like consonants having identity crises. Some of them overlap a lot with voiced fricatives and in some places of articulation, no language bothers distinguishing the two. Don’t worry; we’re not going to be using those crazy buggers. We’ going to use the crazy buggers who can’t quite decide if they’re consonants or vowels: semivowels.

Semivowels are sounds like the y in you and the w in will do as I command. Now which semivowels we have in our language is really going to depend on our vowel system, so unfortunately, we’re going to have to come back to the semivowels next post, but trust me: it’ll be worth the wait.

And with that, we’re onto our last consonant:

7. The Rhotic

If a lateral is an L-ish consonant, a rhotic is an R-ish consonant. Nobody’s entirely sure what makes a rhotic a rhotic. Without throwing a whole bunch of new terms at you, the main unifying property is that they tend to pattern similarly to lateral approximants, but there’s not much else that all rhotics have in common. It’s all very interesting, but not very relevant, so let’s get to it. Rhotics are common cross-linguistically (though there are quite a few languages, most notably in North America, which lack them), with most languages that do have a rhotic having only one. For our conlang, we’ll go with that and we’ll just leave it as a rather ambiguous /r/ for now. Once we get into allophony in a couple of posts, we’ll be revisiting our rhotic and deciding on the particulars of its pronunciation(s).

And that’s our consonants (almost) done. We’ve got a good list now of nine plosives (/p/, /t/, /k/, /b/, /d/, /g/, /mb/, /nd/ and /ŋg/), four fricatives (/f/, /s/, /ʃ/ and /x/), three affricates (/t͡ʃ/, /d͡ʒ/ and /nd͡ʒ/), four nasals (/m/, /n/, /ɲ/ and /ŋ/), two laterals (/l/ and /ʎ/) and a rhotic (/r/), giving us a grand total of twenty-three consonants, plus whatever semivowels we decide to use. That’s fairly respectable.

Before finishing off with the consonant inventory of our language, however, there’s just one thing left to do. You’ll probably notice that we’ve got a pretty nice, orderly system going on here, but natural languages are rarely so tidy (though they certainly can be) and, as some guy said once, I feel like destroying something beautiful… or something like that. So let’s take our nice column of velars (/k/, /g/, /ŋg/, /x/, /ŋ/) and mess it up. A good target is /x/, which can be a volatile sound; instead of having it be a velar fricative, we’ll have it debuccalise to /h/ in syllable onsets¹², palatalise to /ç/ (the h in human) in syllable codas after front vowels¹³ and stay /x/ elsewhere. And that should give you a taste of the allophony we’ll get to start playing with once the basic phonology is in place!

Now, I’ll leave you with this pretty table¹⁴, neatly summarising all the work we just did (click to embiggen).

In the next post, we enter the exciting world of VOWELS!

– Ben xoxo

Notes

¹ Two words differentiated only by a single sound (e.g. cat /kæt/ and pat /pæt/ whose only meaningful difference is the PoA of the initial voiceless plosive: /k/ vs. /p/).

² Conditioned by its environment or just varying freely like some kind of crazy loose cannon phoneme.

³ With /p/ being slightly less common (having been lost in Arabic and a bunch of other languages from around Northern Africa).

⁴ A number of languages (such as Welsh, Icelandic and Burmese) have voiceless nasals, but they’re uncommon cross-linguistically.

⁵ This is both a sweeping generalisation and a vast oversimplification, but at least gives us a starting point.

⁶ We could take /θ/ (the th in think) as the fricative corresponding to /t/, but since it’s a pretty rare sound cross-linguistically, I chose /s/ (probably the most common fricative) instead.

⁷ There are twenty-six consonants if you count the marginal phonemes /ʍ/, which only appears in certain dialects, and /x/, which optionally occurs in a small number of words. To stretch it further, you’d probably have to include interjections like uh-oh/ˈʌ̆ʔ˦əʊ˨/, tut-tut /ǀ ǀ/ or phew /ɧu˥˩/. Accepting consonants in interjections like these would also require you to say that English is tonal and has click consonants, which, though not entirely untrue, would be a misleading to say the least.

⁸ As in the English /t͡ʃ/ (the ch in chair), which developed from palatalised /k/. (In some dialects, the sequence /tj/ as in Tuesday also becomes /t͡ʃ/, while in American English the /j/ is usually dropped.)

⁹ Only about 2% of languages lack nasal consonants and, of these, most have nasal vowels (as in French bon /bɔ̃/), prenasalised plosives or both.

¹⁰ Not to be confused with hellish said by a French or Cockney person.

¹¹ The l in Calrissian is not necessarily [l]; in most dialects of English, an /l/ in the syllable coda is often realised as [ɫ] (a velarised lateral approximant), often called “dark l” (presumably due to its connection with the dark side of the force). /l/ in syllable codas may even lose its lateralisation completely, merging with /w/ or vocalising to [o] or [ʊ].

¹² We’ll get into syllables later, once the basics of our phonology are done.

¹³ We’ll get into vowels next post. Jeez, gimme a break.

¹⁴ Note for the table: /h/ is not technically a fricative, but it is traditionally grouped with the fricatives, so we’ll do so here.

* Opinions may vary as to the epicness of phonology-building.

Let’s Conlang – Part I “Crash Course Phonology”

Salutations, Brain Exchangers! Welcome to my all new blog series: Let’s Conlang! In this series, I’ll be going step-by-step through one of my all-time favourite hobbies: conlanging. (Note: this is an introduction; the actual conlanging will start next post.)

So, wtf is conlanging anyway? It might sound like some kind of obscure sex act¹, but the truth of the matter is far less exciting than that. Conlanging is simply the process of creating a conlang (a constructed language) and in this series, I’ll be going step-by-step through that process, with you, specifically you, the person reading this right now!

You’ve probably heard of some conlangs before (unless you’ve been living sub lapide for the last umpteen years), even if you haven’t come across the word. Probably the most (in)famous example is Klingon, the language of the Klingons from the Star Trek universe. Next most well-known is probably Quenya, one of the many languages Tolkien created for the denizens of Middle Earth. These kind of conlangs, designed to imitate natural language and enrich fictional worlds, are often called artlangs, in contrast to other conlangs, such as Esperanto, which are designed to be used as International Auxiliary Languages. As useful as something like Esperanto may (or may not) be, we’re not about being useful here – we’re about having fun – so in this series we’ll be focussing on constructing an artlang.

Anyway, enough yackety-yak, let’s get to it!

Where do we start?

Like any creative endeavour, starting out a conlang can be a little daunting. Natural languages are huge, complex systems which have evolved over many thousands of years and we’re expected to single-handedly create one from whole cloth? Well, yes and no. A constructed language will never have all the nuances of a natural one, just like even the best painting doesn’t contain every detail of the real world. It only needs enough detail².

“But,” you say, rudely interrupting my monologue, “none of that tells me where to start.”

This is true. Sorry about that. I suppose I got sidetracked. Which gives me a great opportunity to make another point: getting sidetracked whilst conlanging is one of the best ways to get the necessary details in there. Maybe I got sidetracked on purpose just to make that point³.

The most sensible place to start is with phonology, which, admittedly, I kind of gave away in the title of this post. Phonology, for the non-linguistically inclined, is the systematic organisation of a language’s phonemes. Phonemes I’ll get to in a moment, by for now, just read it as “sounds”. There are two main reasons that I like to start with phonology, one artistic, the other pragmatic. Artistically, the choices you make in a language’s phonology are going to have the biggest effect on its sound, which will give you direction for other aspects of the language. Pragmatically, the phonemes of a language are its fundamental building blocks, so, yeah … probably best to get them done first.

So, phonemes are important, but what are they? I could write a whole blog post answering that, but it would be boring and, for our purposes, largely superfluous. In a sentence: a phoneme is the smallest meaningful unit of sound in a language.

As an example, let’s use the English phoneme /t/. Mostly, we think of it as the sound of t in top (aspirated voiceless alveolar plosive [tʰ]), but phonemes don’t just have one sound, they also have allophones (literally “other-sounds”) which are either conditioned by the environment they appear in (e.g. the t in stop, which loses its aspiration, becoming [t]) or just in free variation (e.g. the final t in foot may be aspirated [tʰ], unaspirated [t], preglottalised [ʔt], or replaced with a glottal stop [ʔ] all without altering the meaning). If we want to add even more complexity, in most dialects of American English intervocalic⁴ /t/ (as well as /d/) becomes an alveolar tap [ɾ], meaning an underlying /t/ can be realised as upwards of six different phones (sounds).

Now, if you’re not familiar with linguistics, that last paragraph may have been a little confusing with all that “aspirated voiceless alveolar plosive” nonsense, but terms like this aren’t half as complicated as they seem. It’s just a description of the various phonetic properties of the sound. “Aspirated” means that it’s pronounced with a burst of air (like you feel if you put your hand in front of your mouth and say puff out the candles on the pink pig cake); “voiceless” means it’s pronounced without vibrating the larynx, as opposed to /d/, which is voiced (say tug and dug next to each other; the main differences are aspiration and voicing⁵); “alveolar” means that it’s pronounced with the tongue up against the alveolar ridge (the sticky-outy bit behind your upper teeth); finally, “plosive” means that the vocal tract is completely blocked to make the sound.

OK, deep breath. That probably seems like a lot of work to describe something as simple as the sound t. We don’t want to have to say “aspirated voiceless alveolar plosive” every time we want to talk about a t. And that’s why we have (drum roll) the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)! TA DAA! In the IPA, “aspirated voiceless alveolar plosive” is simply [tʰ]. Now, I’m not going to tell you to memorise the entire thing, but it wouldn’t hurt to spend some time familiarising yourself with it. That massive Wikipedia article might make it seem very confusing, but all you really need to know can be summarised in this simple table:

Looking at the consonants, along the top are the places of articulation (where your tongue/lips is/are⁶) and down the left are the manners of articulation (how you make the sound).

Here is a nice interactive IPA chart which let’s you hear the sounds too.

Note: when playing around with phonology, you will want to say the sounds aloud, which can be very useful; however, be aware that you will sound like a complete idiot. This is unavoidable.

For now, I’ll leave you with that.

If you want, spend some time getting to know the terms and symbols of the IPA; we’ll be using them quite a bit in the posts to come. If not, no sweat; you can just sit back and enjoy the ride.

This introductory post has been largely non-technical. If you’re not so happy about that, don’t fret; the next post will get into the nitty-gritty of conlanging and we’ll start work on the phonology of a brand new language. If, on the flip side, you’re worried about getting in over your head, there’s no need for that either; Any technical term I use, I’ll give a definition for in the footnotes, or I’ll link you to its Wikipedia page.

Click to continue to Part II, where the real fun begins!

– Ben xoxo

¹ Or maybe I just interpret everything as some kind of obscure sex act.

² What constitutes enough detail is going to vary depending on more factors than I care to list (e.g. what you want to achieve with the language, how much you care about details, how much free time you have, etc.).

³ I didn’t.

⁴ Appearing between two vowels.

⁵ Actually, voiced consonants in English are often partly devoiced when appearing word-initially, but we’ll just ignore that for now.

⁶ Except in the case of the glottal consonants which can be thought of as having no place of articulation or an undefined place of articulation.

Brain Exchange S02E04

Brain Exchange – S02E04 (Perma Download Link)

Articles and websites discussed in this episode come from the following:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humanzee

![IPA2005_1000px[1]](https://brainexchangepodcast.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/ipa2005_1000px1.png?w=584&h=755)